League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters of New Jersey was founded in 1920 as a successor to the New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association. Like the national organization, the New Jersey league had a dual purpose: citizen education and the advancement of legislative goals determined by a consensus of the membership.

Photograph, Leaving Newark for the National Convention, 1960

LWVNJ Collection

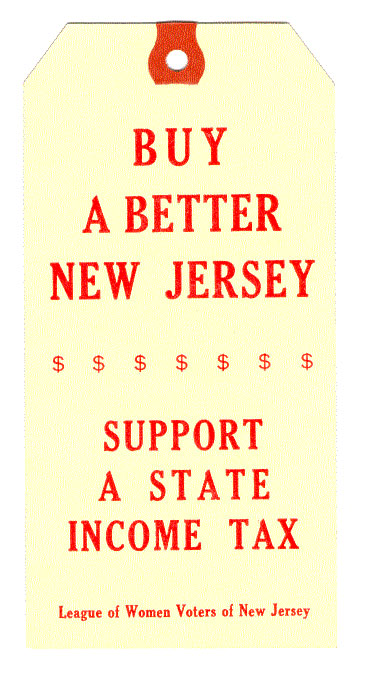

Broadside, Buy a Better New Jersey, 1965

LWVNJ Collection

hotograph, Grace Hopkins handing gavel to Jessamine Merrill, 1951

LWVNJ Collection

Trenton social worker and community activist Jessamine Merrill (1905-1996) served as president of the League of Women Voters of New Jersey from 1951 to 1956. Here she accepts the gavel of office from her predecessor, Grace Hopkins.

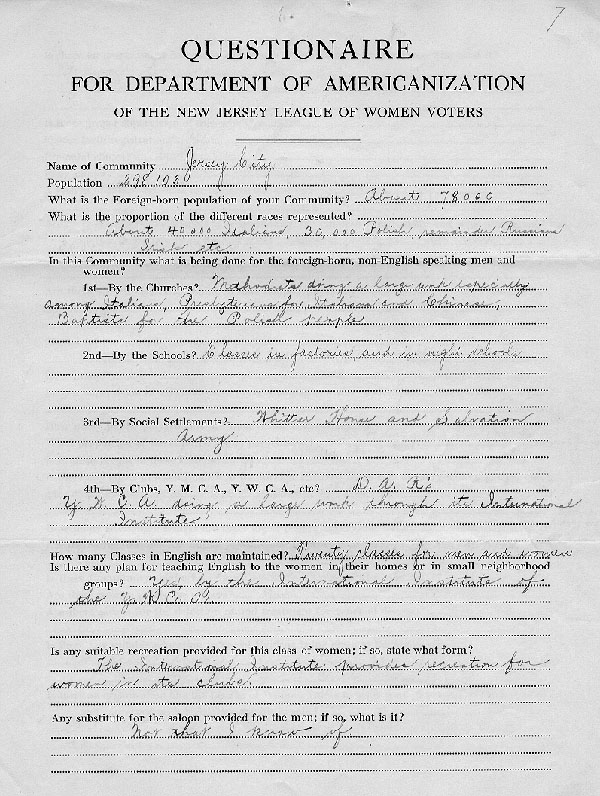

Questionnaire for the Department of Americanization, 1922

LWVNJ Collection

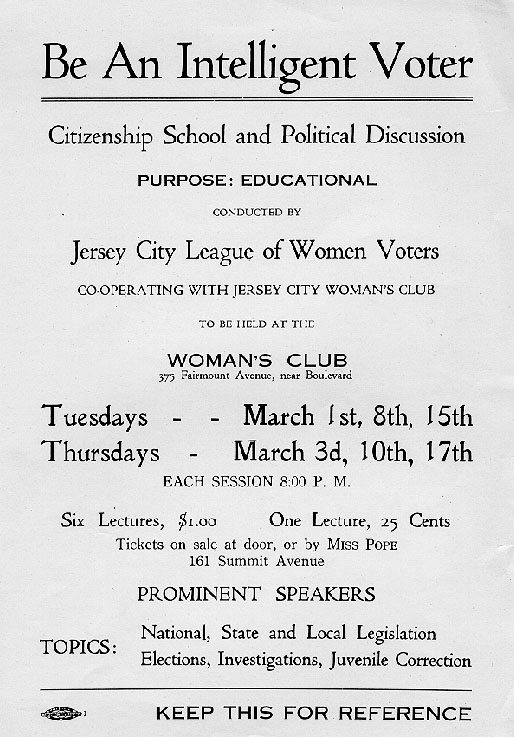

One of the most important roles of the League of Women Voters is non-partisan political education. In 1920, after women received the vote, the League sought to educate women for their new role by setting up “citizenship schools,” which were maintained throughout the decade. The League sponsored registration drives, conducted house-to-house canvassing, and distributed information to election workers and citizens. As shown by this questionnaire, the League also became concerned with the political education of recent immigrants, who thronged New Jersey's cities during this period.

Broadside, Be an Intelligent Voter, 1920

LWVNJ Collection

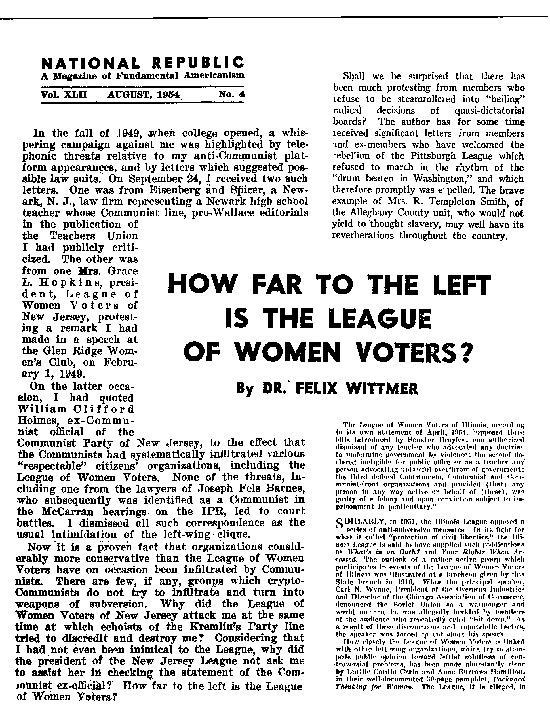

Felix Wittmer, “How Far to the Left is the League of Women Voters?” National Republic 42(4) (August 1954), reprint

LWVNJ Collection

In 1954, the president of the League of Women Voters of the United States launched a nationwide discussion program on individual liberties, known as the Freedom Agenda. As part of this program, local leagues prepared pamphlets on the Bill of Rights, freedom of speech, and other topics. The League conceived this program in response to the Congressional investigations of the period, which it feared were compromising the principles of freedom of expression and freedom of education. The Freedom Agenda itself was criticized by the Un-American Activities Committee of the Westchester, New York American Legion, who accused the League of attempting to show that communism was non-existent. The State and a few local leagues in New Jersey were also attacked during this period. In 1949, Felix Wittmer, a history professor at Montclair State College, claimed that the League was being infiltrated by communists. However, as had been the case with similar attacks during the Red Scare of the 1920s, these accusations seemed to have little impact.

Portrait, Louise Steelman, undated

LWVNJ Collection

Louise Steelman of Montclair served as chairman of the League's Committee on the Legal Status of Women, founded in 1927. This committee was charged “to secure for women a larger freedom and a true equality with men before the law.” It studied marriage and divorce laws, property rights, women's employment, the care of women offenders and many other issues. In the mid-1930s, Steelman led a campaign to secure full equality for women in jury service. Although women were legally entitled to serve on all jury panels, a League survey revealed that a few counties (particularly Essex, Mrs. Steelman's home) did not include women on their jury lists. In conjunction with Federal Judge William Clark, Steelman arranged for jury schools to train citizens and promote women's participation in juries. In 1937, Clark appointed Steelman as the first woman Jury Commissioner in the country.

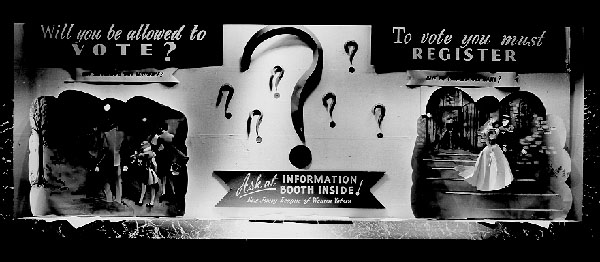

Photograph, “Will You be Allowed to Vote?” ca. 1946

LWVNJ Collection