Free and Fair Elections

In the most general sense, political scientists understand a free and fair election to be one in which voters have the right to choose their candidate or party without fear or intimidation, where all political parties have the right to campaign and communicate freely to voters, and where every vote is tallied.

Not all Americans have had access to free and fair elections. At the time of the founding of the United States, most states restricted suffrage to white property-holding men, and it was not until 1856 that property qualifications were eliminated in all states. In 1870, the 15th Amendment’s passage prohibited federal and state governments from denying the right to vote to male citizens based on race. Wyoming became the first U.S. state to grant women the right to vote in 1890, but it took until 1920 for all American women to gain the right to vote and, for Black women, this right applied more in theory than in practice. In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act made Indigenous Americans citizens, but many state-level discriminatory policies still left them unable to vote. The 1965 Voting Rights Act did away with poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses. However, voter ID laws, gerrymandering, and the targeted removal of voters from voting rolls have led many scholars to argue that fair elections still remain a goal rather than a reality.

Separate from these government-backed exclusions, the history of voting in the United States has also been marked by more informal, yet equally pernicious, attempts to deny individuals their vote. Until the twentieth century, voting took place in taverns, grocery stores, and other private establishments, where anonymity could not be guaranteed and coercion was often rife. “Cooping” involved drugging and kidnapping voters to get them to cast their ballot for a certain party. Gangs engaged in brawls to block opposing voters from accessing polls. Employers used subtle and explicit forms of pressure—a practice that continues today—to coerce workers into voting for certain candidates.

This section explores how different interests have tried to restrict the vote and how voters have responded in fighting for their rights.

--Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives - Museum Objects Collection; Contributor: Tara Maharjan

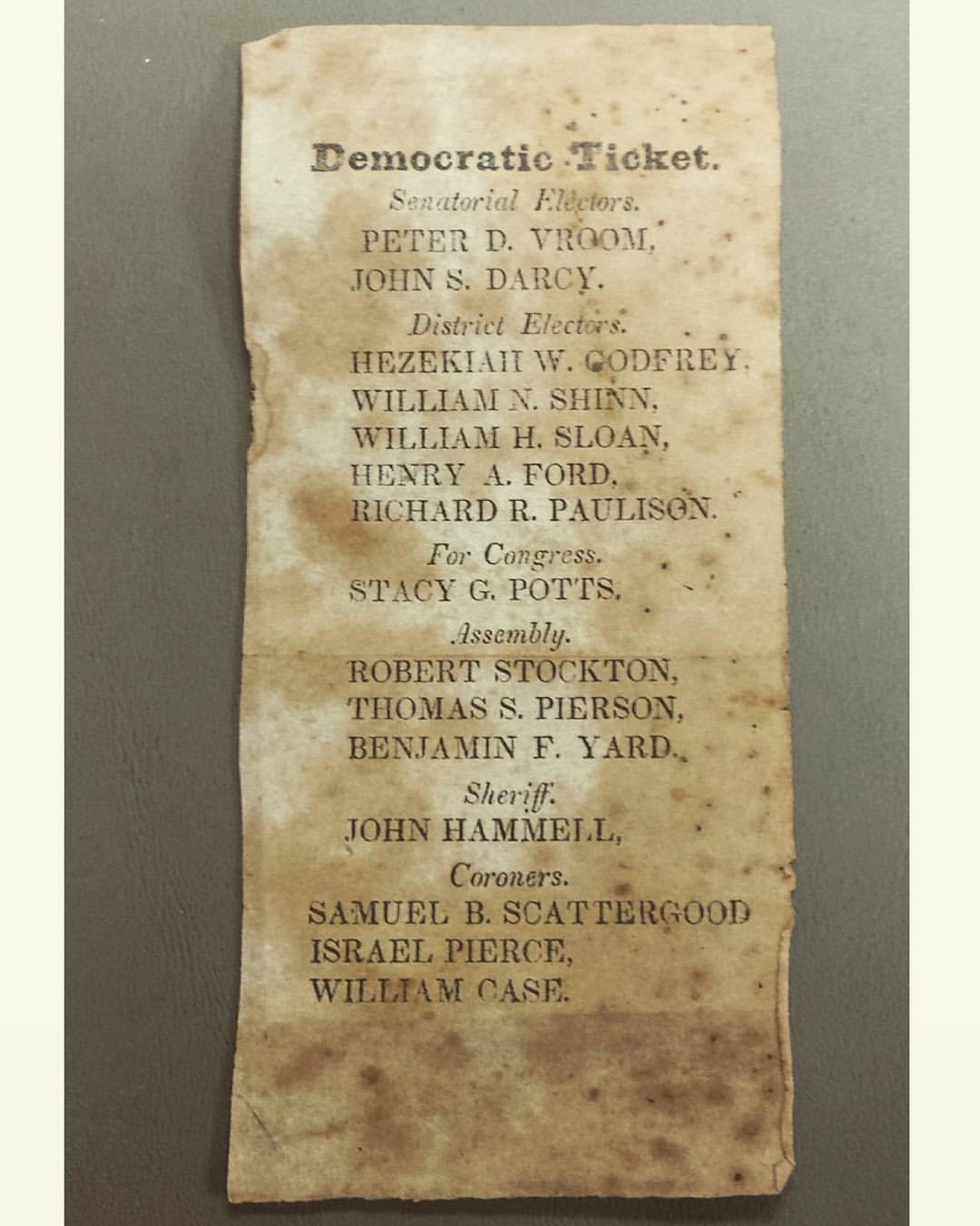

This 1839 New Jersey democratic ticket was found as a bookmark in a circa 1825 "The Publications of the American Tract Society."

This small paper New Jersey Democratic ticket from the 1839 election shows the slate of candidates and the different offices in which the Democratic party was contesting. Tickets like this one listed the candidates endorsed by the party and since early paper voting entailed the voter simply writing their vote on a paper and dropping it into a box, people were encouraged to simply drop their ticket into the voting box. An example of a voting box can be seen elsewhere in this exhibit. More information about the history of paper ballots can be found here.

--Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives - New Jersey Ephemera Collection; Contributor: Tara Maharjan

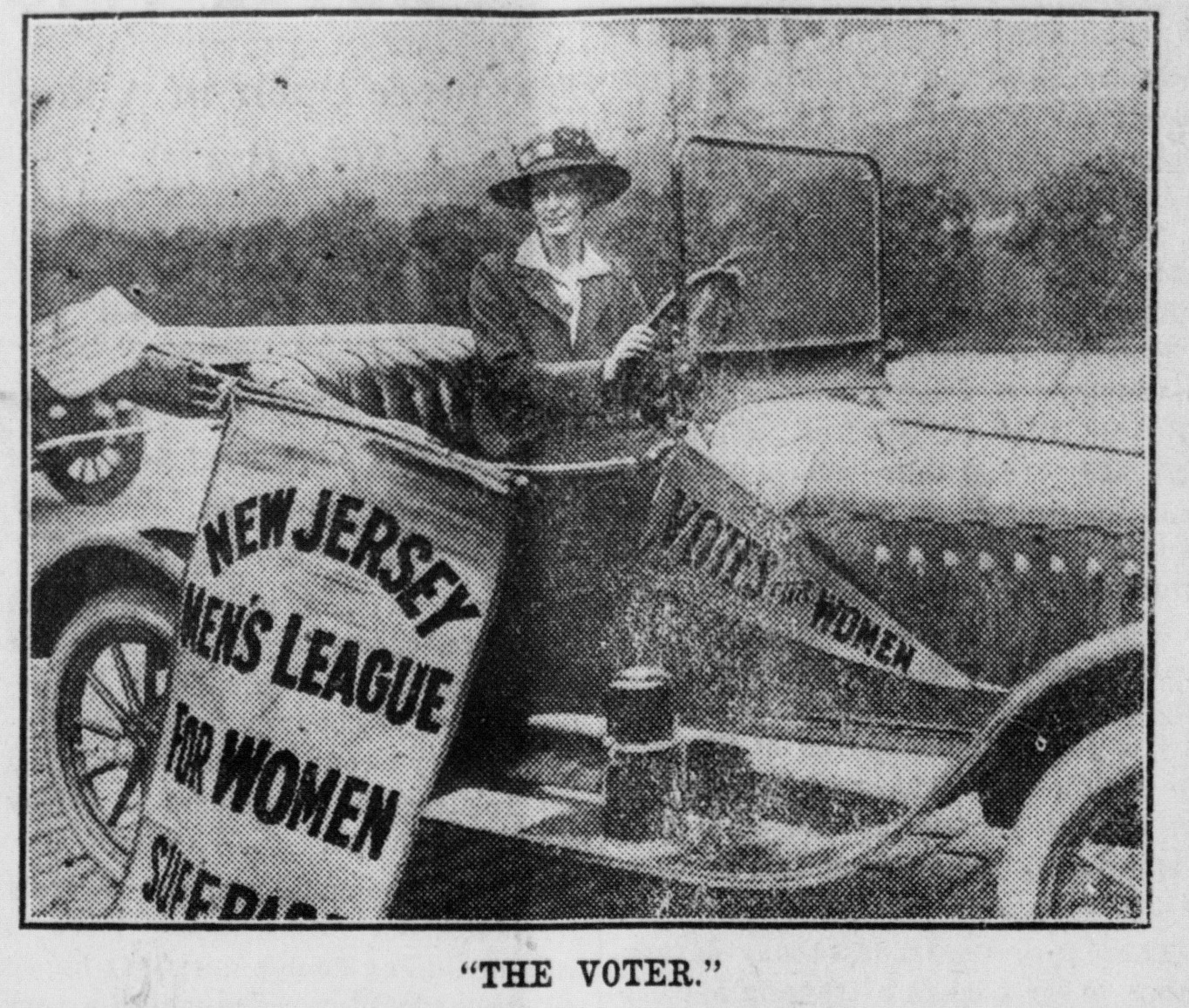

Photograph from Bridgeton Pioneer featuring Eva Ward, a British suffragist who became active in New Jersey’s efforts for suffrage, June 3, 1915.

The limited voting rights New Jersey women had been granted in the state’s 1776 constitution were revoked by the State legislators in 1807. The subsequent campaign for women’s suffrage in New Jersey was long and unsuccessful until the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920. New Jersey’s newspapers covered and reflected changing attitudes towards suffrage, featuring stories and editorials on the efforts to win the vote for women. Some newspapers, such as the October 29, 1912, Newark Evening Star and Newark Advertiser published special suffrage editions featuring women writers and editors. With a 1915 referendum on voting rights for women on the ballot in New Jersey, newspapers carried daily stories demonstrating efforts of suffrage advocates and the ultimate defeat of the measure. Eva Ward, a field worker for the New Jersey Men's League, whose photograph appears in the June 3, 1915, Bridgeton Pioneer and the August 13, 1915, Newark Evening Star and Newark Advertiser further challenged attitudes about women’s abilities by using a relatively new innovation, a yellow automobile named “The Voter” as her peripatetic office in her campaign. In this June 3, 1915 article, Ward announced her intention to stop at factory gates and speak to working men during their lunch breaks

--Bridgeton Pioneer, Chronicling America; Contributor: Caryn Radick

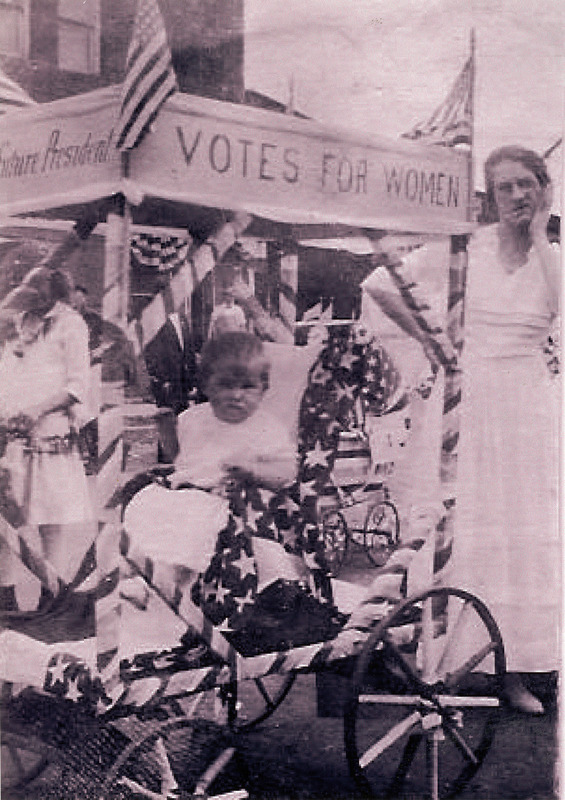

The image features June Sicknick with her mother Edna Keller Sicknick. The carriage with the slogans “Future President” and “Votes for Women” was decorated for the baby parade held on September 25, 1920, as part of the celebration for South River’s 200th anniversary. June was born on November 19, 1919. While she didn't make it to president, she did go on to graduate from the New Jersey College for Women and become a technical librarian.

The fight for women’s suffrage engaged women from all walks of life. Sarah Evans Selover, a local physician, was one of the leaders of South River’s Equal Suffrage League. While many affluent women were often involved in suffrage groups, working class mothers like the one in this photograph also joined the campaign. South River’s women voted in school elections as early as 1913. Seven of the 167 ballots cast that year came from female voters who, according to the newspaper, cast their ballots "without fear or trembling," which the newspaper noted was in contrast to stereotypes about female timidity. Six years later, women cast more than half of the school election ballots. In September 1915, the local suffrage group formed. Such was their success that a month later, when New Jersey put the issue of suffrage to a state vote by the people, the suffrage amendment was rejected by a margin of one vote in South River. The rejected amendment represented a major turn for a place that was expected to follow the majority of the state. After the 19th Amendment became federal law in August 1920, South River women were quick to take advantage. 265 South River women voted in the primary election in September, and 535 voted in the general election in November.

--South River Historical and Preservation Society, Inc., 9/25/1920; Contributor: Stephanie Bartz

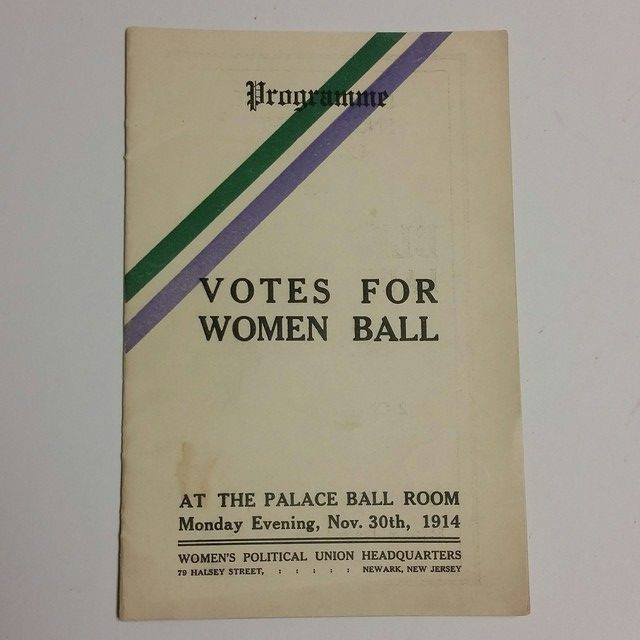

Program for the Women's Political Union’s Votes for Women Ball held at the Palace Hall Room in Newark, New Jersey, on November 30, 1914. For more information about the Women's Political Union, please see "The Woman's Reason" broadside in this exhibit.

--Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives; Contributor: Tara Maharjan

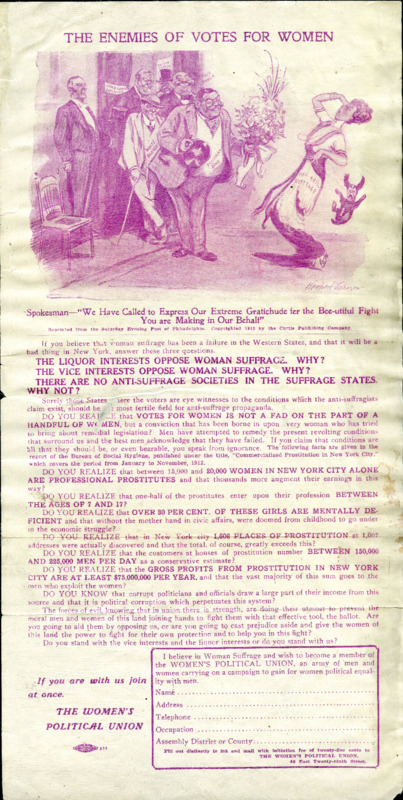

Advertisement by the Women’s Political Union to gain support for the women’s suffrage movement, 1913.

In early 20th century, different women’s groups in support of suffrage competed for membership. This broadside calls for women to join the Women’s Political Union, founded by Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Blatch extended the suffrage movement to the working-class women and became a leader, unifying women from different socioeconomic backgrounds. In 1916, Women’s Political Union merged with Congressional Union, led by Alice Paul, to become the National Woman’s Party.

--Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives; Contributor: Tara Maharjan

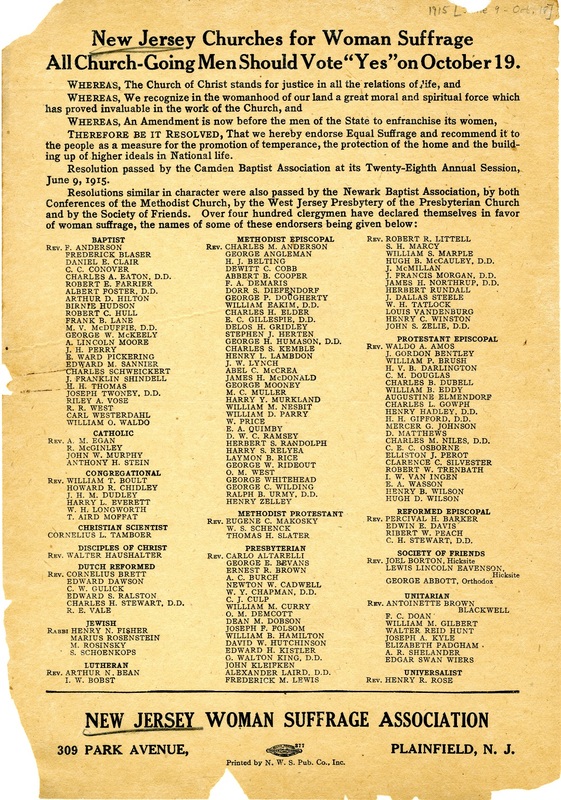

New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association broadside "New Jersey Churches for Women Suffrage," 1915.

The women’s suffrage movement needed support from different groups in order to achieve its goal. This broadside published by the New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association during the campaign for a state suffrage amendment in October 1915, expresses support for the movement from New Jersey churches of different denominations. The clergymen listed, members of the Society of Friends, Roman Catholic Church and different branches of the Protestant Church, endorsed equal suffrage on the grounds that it would promote "temperance, the protection of the home and the building of higher ideals in National life." This association of women's suffrage with the temperance movement probably insured the amendment's defeat, particularly in urban areas.

--New Jersey Political Broadsides, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, 10/1/1915; Contributor: Fernanda Perrone

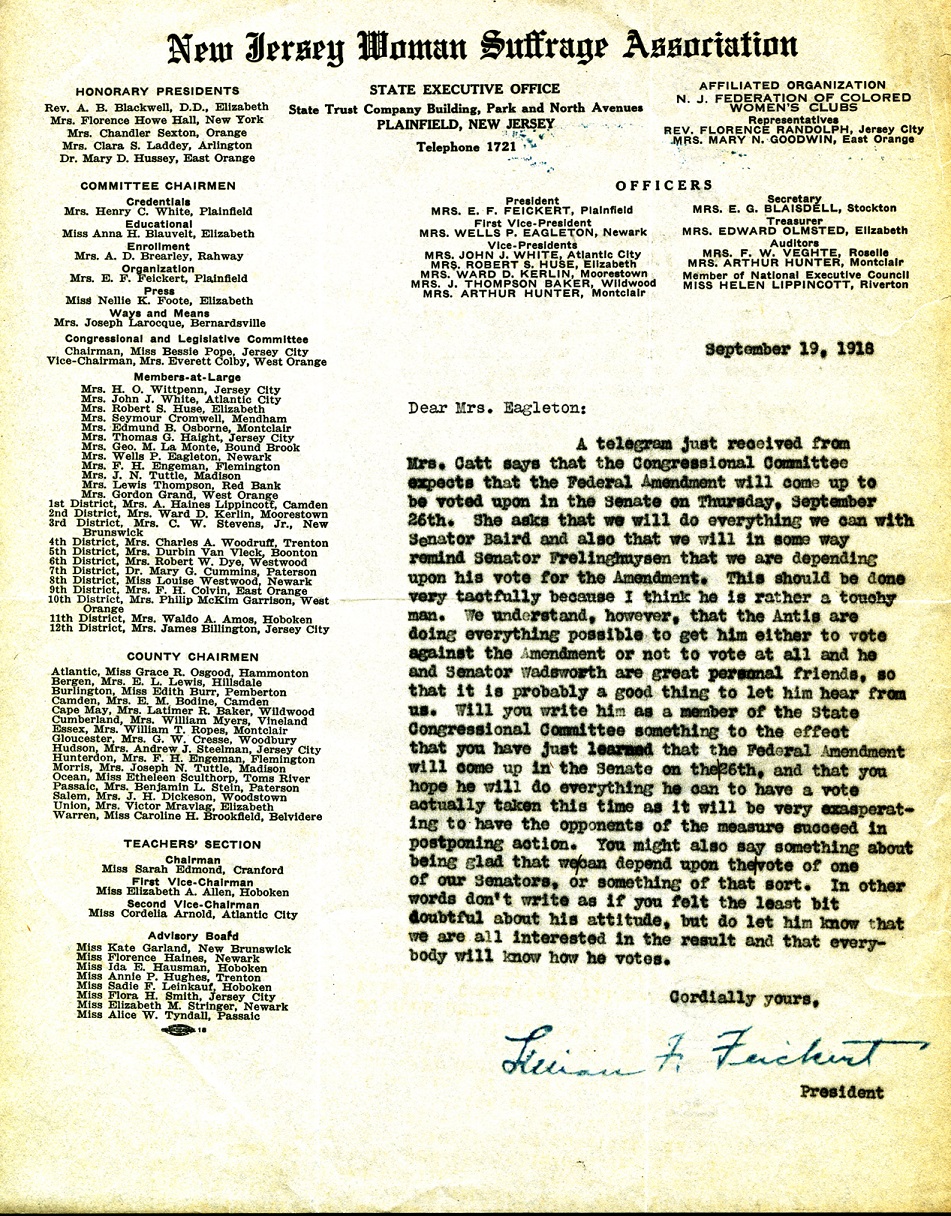

Letter from Lillian Feickert to Florence P. Eagleton, September 19, 1918.

This letter from New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association (NJWSA) President Lillian Feickert to the organization's Vice President Florence P. Eagleton shows that New Jersey women were astute lobbyists during the suffrage campaign. In September 1918, the federal suffrage amendment was up for a vote in the U.S. Senate. New Jersey Senator David Baird was anti-suffrage, while Senator Joseph Frelinghuysen was pro-suffrage, but as the letter states was "rather a touchy man." In the event, the amendment lost due to Baird's negative vote, although it would later pass.

--New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association Records, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries; Contributor: Fernanda Perrone

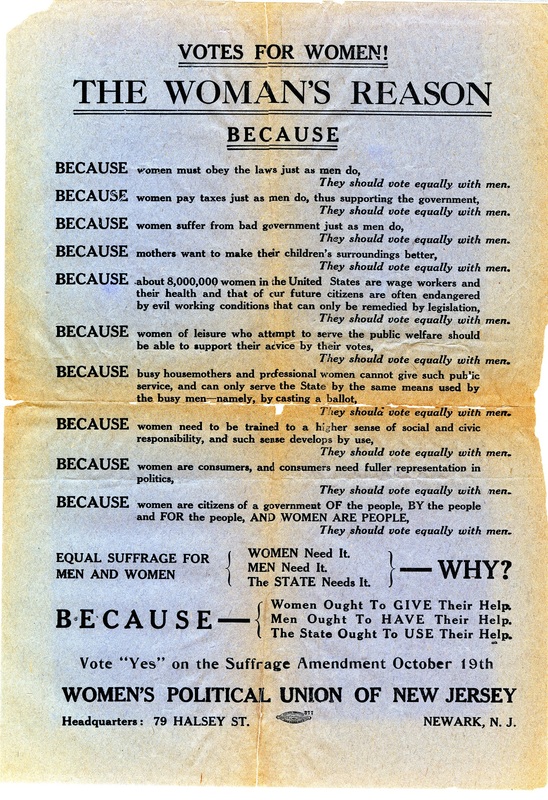

Broadside, "The Woman's Reason," Women's Political Union of New Jersey, Newark, NJ.

This broadside published by the Women's Political Union of New Jersey gives ten reasons why women should vote equally with men. It appeared in conjunction with the 1915 referendum on the state women's suffrage amendment. The Newark-based Women's Political Union (WPU) was a smaller and more radical organization than the New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association. The WPU proved to be particularly adept at publicity during the referendum campaign, although the amendment was ultimately defeated. In 1916, the WPU merged with the New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association, although many WPU members later joined Alice Paul's National Woman's Party. To learn more about the National Woman's Party and Alice Paul.

-New Jersey Political Broadsides, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, 10/1/1915; Contributor: Fernanda Perrone

Postcard, Soldiers Club Conducted by New Jersey Women [sic] Suffrage Association, Wrightstown, NJ, ca. 1918.

The New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association ingratiate itself with politicians and citizens alike by actively supporting the troops during the First World War. In October 1917, the organization began its major war-related project, a soldiers' club at the newly-opened Camp Dix training facility in Wrightstown, New Jersey. Local suffrage organizations took turns serving as hostesses at the club. Apparently, "the house was open for privates only and that any amount of homemade pies and cakes and coffee could be obtained at the clubhouse and that it was filled with every convenience for the comfort of the boys." Although the volunteers were told not to talk to the men about women's suffrage, the subject naturally came up. After all, the name New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association was prominently displayed on the clubhouse.

--New Jersey Postcards, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, 1918; Contributor: Fernanda Perrone