Policing the Boundaries of Inclusion: Citizenship and the Right to Vote

Historically, the question of whether immigrants should have the right to vote in local, state, and national elections was open, with many states granting this right to unnaturalized, permanent residents. It was not until the 1920s that states, which determined eligibility to vote outside of constitutionally protected categories, uniformly purged immigrant voters from their rolls.

Until 1868 and the 14th Amendment’s ratification, Black Americans were denied citizenship despite their birthright. Asian immigrants, due to Congressional statutes that limited naturalization to “free-born whites” and in 1870 to those of African descent, were not permitted to become citizens until 1952. Other restrictions on naturalization disenfranchised Native Americans until 1924.

As this section explores, different groups have engaged in protracted battles for citizenship.. The artifacts below help us consider how the right to vote fits into the larger battle for full citizenship and equality.

Policing the Boundaries of Inclusion: Citizenship and the Right to Vote

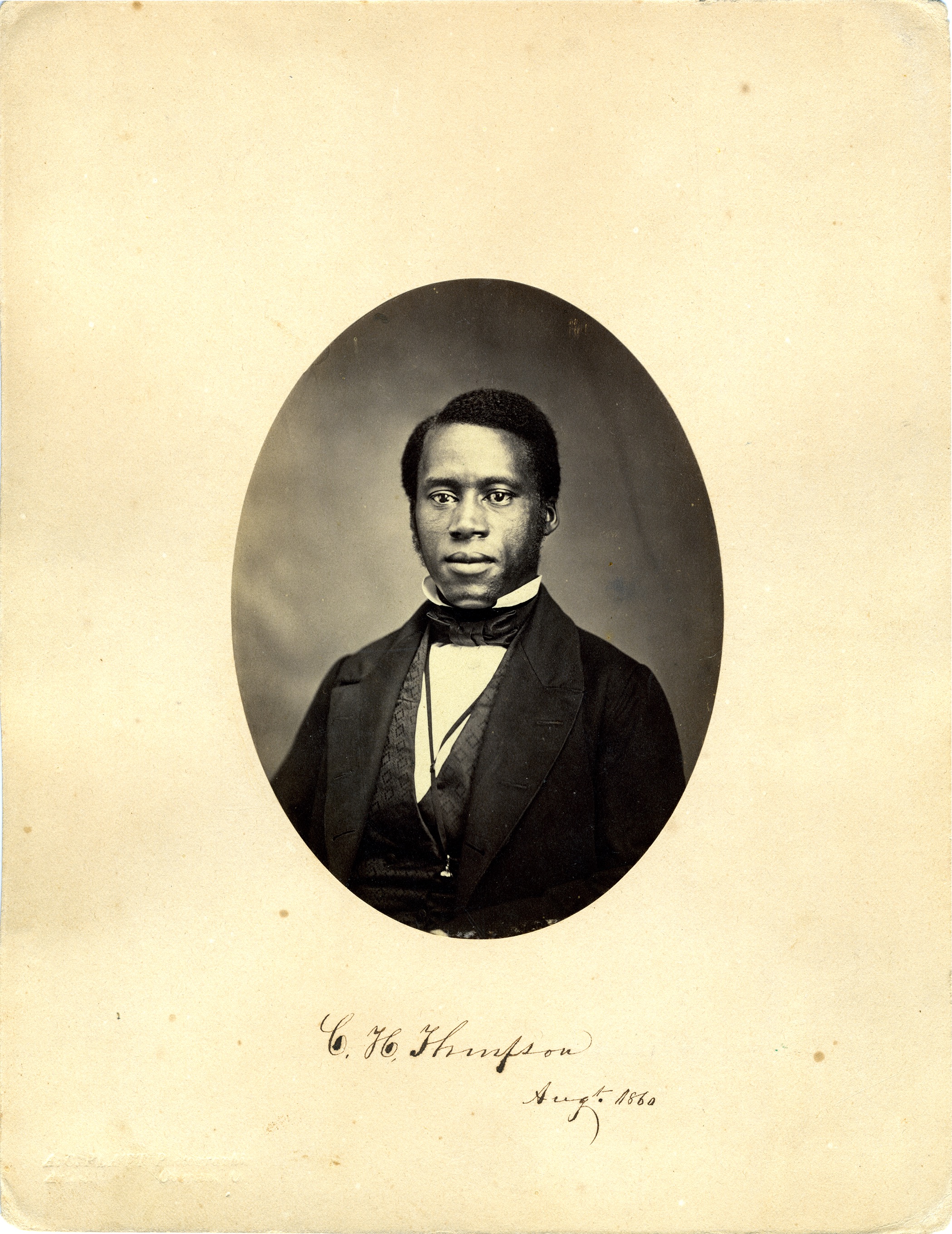

This photograph depicts the Black abolitionist, activist and educator Charles H. Thompson while at Oberlin College. Black suffragist Mary Church Terrell, co-founder of the National Association of Colored Women, graduated from Oberlin too. Both institutionally educated and self-taught activists contributed to the struggle for voting rights, but many of their voices have been overlooked by historians. Thompson and two other New Jersey Black activists were at the center of a campaign in 1860 to challenge the voting law’s unconstitutionality. Thompson, pastor of Plane Street Colored Church, and Abraham Conover were the Newark test plaintiffs and sued for damages of thousands of dollars for being refused the right to vote. Though they lost, their strategy was remarkable. Reflecting the cross-state and national organizing that Blacks had engaged for more than half a century, the council hosted “numerous meetings and the committees appointed at those meetings in the States of New York, Newark, Pennsylvania and Delaware.” The case elevated public awareness and demonstrate Black New Jersey’s resistance against exploitation. This discussion is an excerpt from an upcoming exhibition curated by Noelle Lorraine Williams at Newark Public Library called “Black Power! 19th Century Newark’s First African American Rebellion.”

--Oberlin College, 1860; Contributor: Noelle Lorraine Williams

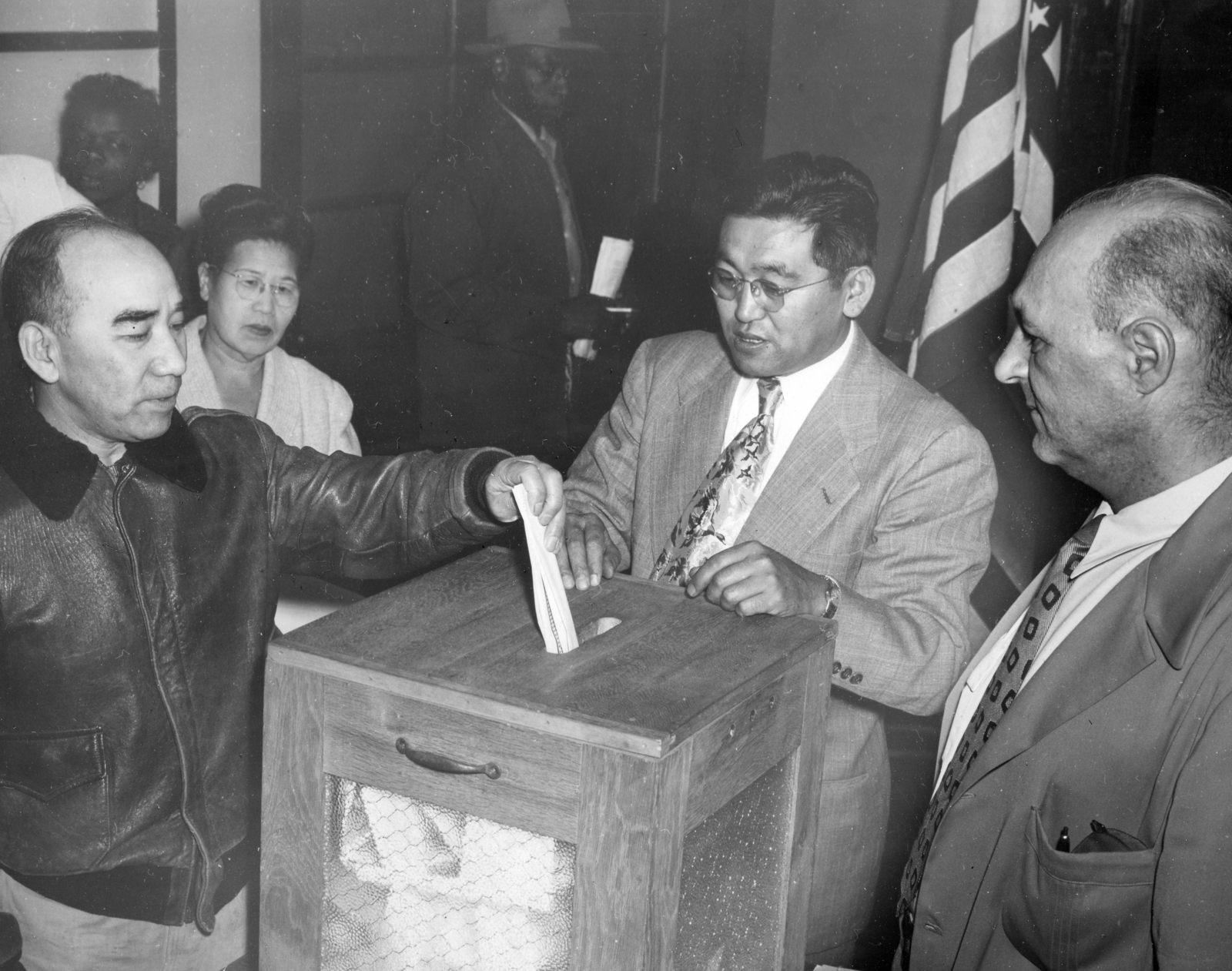

In this photograph, Mitsuzo Funo, a Tenrikyo priest and Japanese immigrant from Hokkaido, who first came to California in the 1920s on a religious visa, casts his first ballot as an American citizen in what was likely the 1954 election. That same year Funo traveled to New York City from Seabrook Farms to bless a Shinto temple that the Museum of Modern Art had imported from Japan. Funo passed away in Chicago in 1986.

As important as the 15th and 19th Amendments were to expanding suffrage, formal discrimination concerning who could become a citizen and vote remained a feature of American law until 1952. That year, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act, which granted Asian immigrants, who had been barred from naturalizing, the right to become citizens. During the Second World War, Seabrook Farms, an agribusiness in Cumberland County, New Jersey, recruited more than 2,500 incarcerated Japanese Americans from concentration camps in the West, to bolster its labor force. While many of the Japanese Americans released to Seabrook Farms left New Jersey after the war's end when they were again permitted free movement, a couple hundred remained with the company into the 1950s. At a naturalization ceremony that the company staged in 1953, Mitsuzo Funo, the man seen voting in the above photograph, was among 127 Japanese immigrants who took the oath of citizenship. I wonder what Funo, who at this point in his life had experienced harassment from American immigration officials, imprisonment despite never committing a crime, and parole to New Jersey, felt about exercising his right to vote as an American citizen? What did it mean to him?

--Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center (SECC) Records, Rutgers University Community Repository Collection, 11/2/1954; Contributor: Andrew Urban