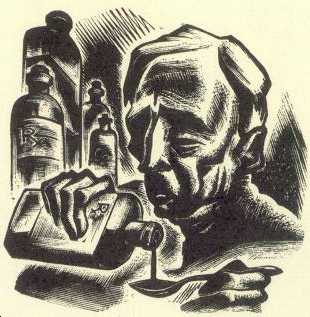

An Elderly Gentleman : IMAGE 76 : Medicate

In I76, the enfeebled Gentleman empties medicine from a bottle into a spoon. Looming over his shoulder, a supply of unopened bottles, constructed like a fortress or a city skyline, suggests that the medication is purposed to block out death, the Unknown, but that perhaps it has become for him yet another of Doom’s many dreadful faces. This is the first small image in the "An Elderly Gentleman" section and follows a jumbo image of the Gentleman standing naked before a mirror, unhappily appraising the effects of advancing age. The sequence indicates that the Elderly Gentleman is fixated upon the appearance of his physical deterioration, and perhaps hints that there is a narcissistic or psychosomatic component to his illness.

(As much is implied in the contrast Ward leads us to draw with I5, an homologous image which falls in the same place in the opening sequence of the first section of Vertigo. Here it is the Girl who is depicted naked; but content with the palpable reality of her good health and beauty, her eyes are closed, her back turned to the mirror behind her.)

I76 also frames an important strategy of signification. Symbols of time appear in the background of the images in this section (note the grandfather clock in I79), carrying the conventional implication of approaching doom, and hinting darkly that doom is always present in the background of the Elderly Gentleman’s thoughts. The manmade timepieces (memento mori) pose a contrast to the shining star image in section one (see above: I30, I60). Just as The Girl is characterized in terms of nature, the immutable universe, bright and lofty hopes, the Elderly Gentleman is characterized in terms of artificiality, the exhausted, moribund world, and despair.

The Gentleman’s struggle with death, and its ultimate impact on the relationship of The Girl and Boy can be seen as two sides of what Philippe Aries conceptualizes for us as one problem. Aries writes that, early modern society created a system of defenses—among them religion, morality, government, law, even technology—against the uncontrollable forces of nature; but these defenses were not impregnable: "This bulwark erected against nature had two weak spots, love and death," through which the savage forces of nature could break through.3

As a threat to nature, modern society exists as a target for a kind of Romantic fury throughout Ward’s graphic novels, beginning with Gods’ Man and continuing through the final book he was developing at the time of his death, in 1985.4 In Vertigo, Ward seems to be arguing that, in its struggle to prolong life unnaturally, and thus to defeat nature, society’s systems and institutions materially benefit the elite, while they forfeit some essential, ontological good—a connection to Being—and thus imperil the whole of the human community. I am suggesting that Ward is not merely telling us that erotic union is an advance casualty of this imminent collapse, but is the designated sacrifice, since it offends against society, according to Aries, by bodying forth the same savage forces that threaten its hegemony. The attacks upon nature-as-death and nature-as-love are reciprocal.5

Since it is very much the intent of Vertigo to argue on behalf of those forces, its task is to delegitimize the Elderly Gentleman’s will to live, or somehow ally the reader’s sympathies with the ‘natural’ death he contrives to cheat. The Elderly Gentleman thus becomes another example of the Gothic monster, who, like Goethe’s Faust and Shelley’s Frankenstein, must be seen to relinquish a moral claim in pursuit of its hyper-extended longevity. In fact, Ward illustrated both Faust and Frankenstein during the early 1930s (the same decade he created Vertigo), and it is obvious that the affinities between this picaresque character of immoderate longings and Ward’s vision of society as a dangerously unnatural force were nurtured during the process.

Ward’s last unfinished novel also portrays temporality as a post-Lapsarian world of large, numberless cogs, into which innocent Man inevitably tumbles and wherein he will toil without pleasure or point. Ward’s preoccupation with time as meaningless suffering is also exemplified in the "An Elderly Gentleman" section by its division into 12 parts, which are represented by the months of the year—the traditional correlate to a human lifespan. By contrast, the last section of Vertigo, "The Boy," is divided into 7 parts, corresponding to the days of the week—a Western symbol of The Creation.

Notice that, in contrast to the small images of the preceding section ("The Girl"), the texture of the clothes, hair and the surfaces of all other objects here almost utterly lack detail. The dynamic curls and contrasts that epitomize the vivacity and unpredictability of youth are absent from the world of the Elderly Gentleman, and the prevailing color here is a charcoal smudge. The narrowing of the block further emphasizes the Gentleman’s shrinkage from life.

Print view