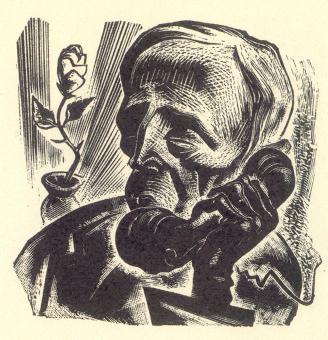

An Elderly Gentleman : IMAGE 96 : Placing the Call

The angriest chapters of Vertigo are concerned with labor issues, beginning with the second image of the chapter entitled "March," I96, in which the Gentleman places a telephone call. In a violent passage comprising 32 images, in which striking workers and union organizers are shown being pummeled, mauled and ultimately bayoneted to death, the repeating image of the Gentleman placing a phonecall accrues to itself the force and authority of a poetic refrain, and endows this electrifying passage of the novel with an autonomous, ballad-like quality. It concludes, anti-climactically, when the Gentleman (finally) places the phone back on the cradle in I127, a kind of coda.

In I96, the telephone is introduced as an instrument of secrecy and death, a counterpoise to the symbol of the rose, which the Gentleman carries in I67, the first image of this section, to signify that he bears responsibility for nurturing the future. That is in fact the cultural meaning of his wealth. In I30, roses appear as proof of The Girl’s artistic triumph, and in I40, a single rose sits in a pot on her windowsill, beside her violin and open sheet music, signifying The Girl’s artistic promise, or her potential for meaningful growth. The rose also appears as a more complex symbol of growth in I57, in which The Girl’s father contemplates suicide. As an image in the background, the rose ambivalently figures as a symbol of The Girl's promising future, to further which the father would sacrifice his life, or as a symbol of life, itself--a call to remain alive and therefore to protect The Girl by remaining her father. Here, in I96, the suggestion is that the Elderly Gentleman is turning away from his responsibility to society, and the dictates of his own conscience, in order to pursue secretive and deadly ends.

Ward’s evident animus toward the telephone can best be understood by comparison with contemporary antipathy toward email and other mediated communication. Telephones enable distanced and therefore depersonalized contact, effectively buffering users from the immediate consequences of their verbal acts. In its time, Ward’s construction of the telephone as a dystopian agent was no more idiosyncratic than similar constructions of the internet is in ours. While Karl Marx feared what is now sometimes called "the new work culture," believing that the telephone was a tool by which the bourgeoisie could further exploit the worker, Theodore Adorno, in a famous essay, "Dialektik der Aufklarung," or "The Culture Industry," originally published in 1944,7 mades the point that the telephone was among modern-day conveniences that "bear witness to man's attempt to make himself a proficient apparatus" at the expense of our humanity. Though cultural studies now tend to take a rosier view, theorizing the telephone and telephony as mediating a space in which reductive social constructions such as gender, class and race can be annulled, or reconstructed more benignly, Adorno’s belief in 1944 was bleaker. Humanity reproduces within itself the bluntness and soul-killing "proficiency" of the mechanical devices it fashions for its pleasure.8 (And let us note in passing that in I51, The Eagle Corporation replaces The Girl’s father with a calculating machine, effectively sentencing him to starvation.) 9

In contrast to the spiritual and organic rose, the telephone is thus an agent and symbol of dehumanization and oppression, similar to and more lethally configured in the gun and the bayonet.

Print view