Seventh Annual New Jersey International Book Arts Symposium

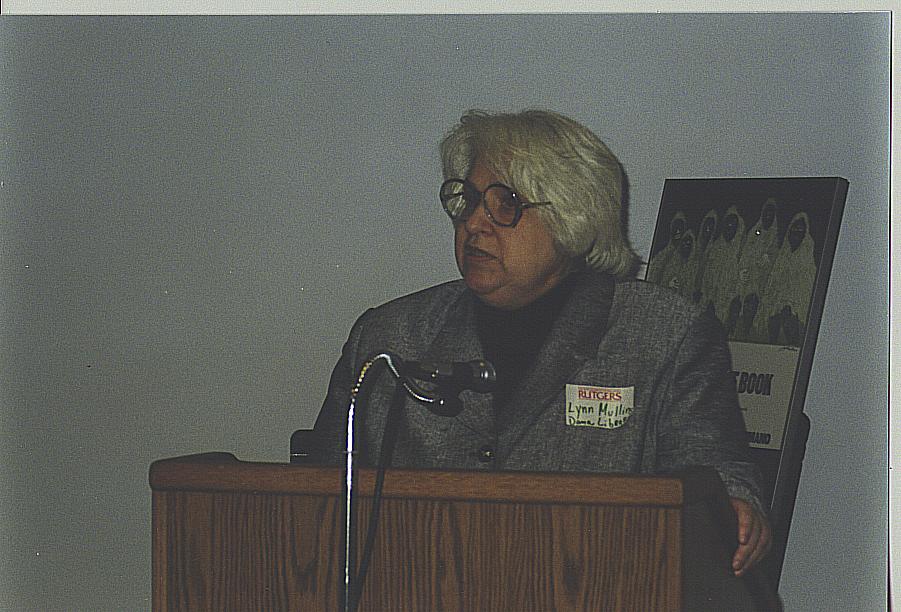

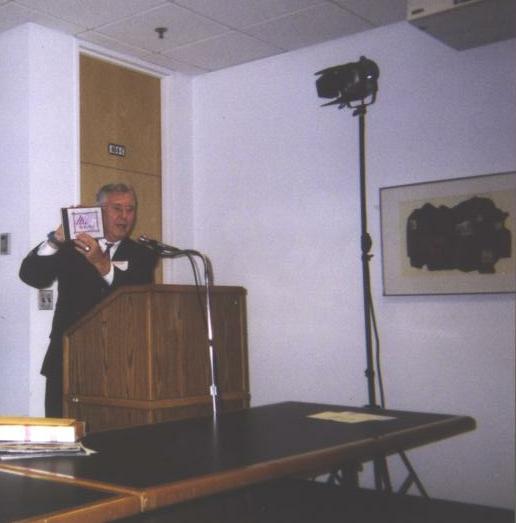

Photos: Welcome

Immediately following Lynn S. Mullins' welcoming remarks, the morning's Master of Ceremonies, Bill Dane drew upon the riches of the Newark Public Library to demonstrate the international scope of what he called "the artist's book movement." As he has done for six of the seven years the NJBAS has been in existence, Dane then introduced the New Jersey artists who formed the panel of morning speakers. The first speaker was the Swiss born painter/artist Gérard Charrière. Charrière spoke of powerful moments in his life to which his art constitutes a lyrical and deeply personal response, and emphasized the artistic responsibility of perfecting one's technique. Charrière's whimsical and delicate imagery (e.g., his use of hair, driftwood and other fragile discarded/found objects) in combination with rich, saturated, color and heavy, abrasive materials, such as sand and stone, imbue his unique work with contradictory sensations of evanescence and obdurate durability.

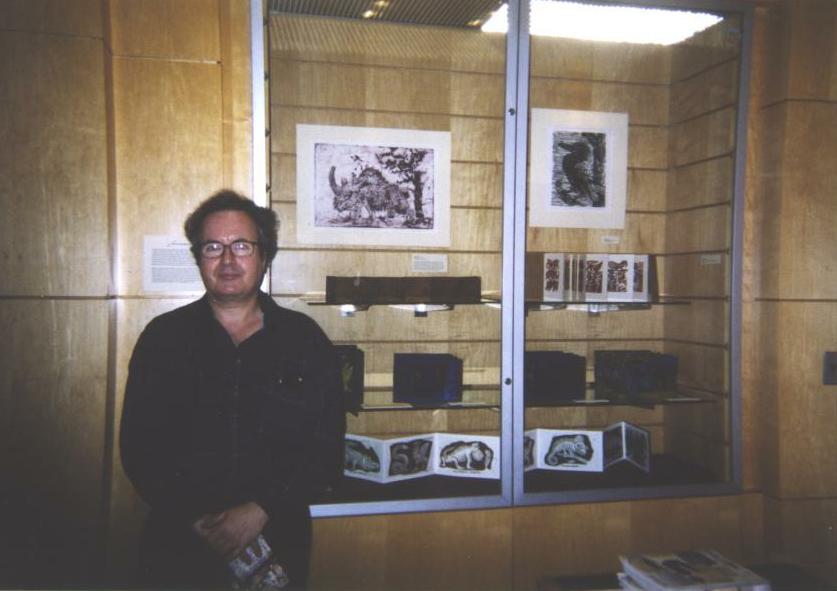

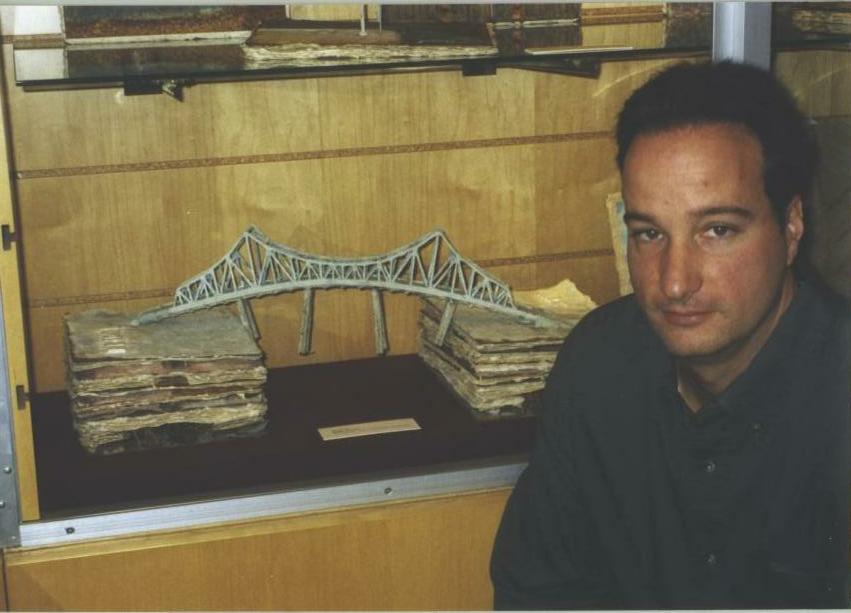

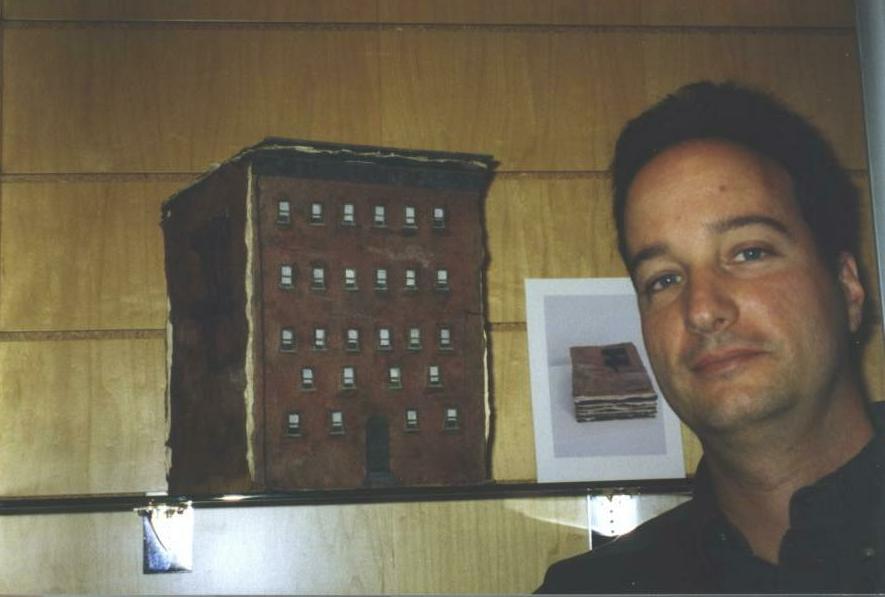

Rand Huebsch echoed Charrière's valorization of technique by examining methods of printmaking and the various effects achieved by different papers and metals. He conspicuously walked around questions of content. The strange beasts (Medieval beastiary, Blake, Sendak?), which look out silently from his timeless prints and tunnel books were given to the audience to decipher, without any authorial gloss or mediation. Rocco Scary, a book artist/sculptor who constructs bookworks from metal and handmade paper (primarily), related how destiny in the form of a capricious college advisor at Montclair State College introduced him to The Book. Aspiring to take a class in sculpture, Scary was encouraged to take papermaking instead, and did. He clearly brings to paper a sculptoral point of view. Privileged to have been taught by the late Suellen Glashausser, Scary's books seem to be grounded in early twentieth century urban avant garde--the work of the Ashcan School, for example. When they are opened, his books resemble homemade models--of bridges, taverns, apartment houses--pervaded by the bluesy ambience of life in a small city. They convey a contradictory sense of safety in melancholy neglect and plainness. But Scary's installations fold up and stack like the leaves of a book; they open and close, and thus the objects that model a life are self-conscious symbols, and, pointedly, there is a tension between the indeterminacies of text and the solid physicality of things in the world.